Media › Forums › The Uganda Useless Elite Class › Yoweri Museveni is the Biggest Parasite in Uganda › Reply To: Yoweri Museveni is the Biggest Parasite in Uganda

50 years of Ugandan independence

British rule over Uganda came to an end on October 9, 1962. Half a century later, the African nation still has not made the transition to genuine democracy.

In the early years of the 20th century, Winston Churchill, Britain’s World War Two prime minister, described Uganda as the pearl of Africa. These days it is regarded as one of the more politically stable countries on the continent. In spite of corruption, annual economic growth has clocked in regularly at between five and seven percent and large oil deposits hold out the prospect of even greater riches. Uganda has won international recognition for its large troop contingent participating in the African Union’s peace mission in Somalia. And yet the pearl is not as bright as once was.

Uganda is engaged in AU peacekeeping in Somalia

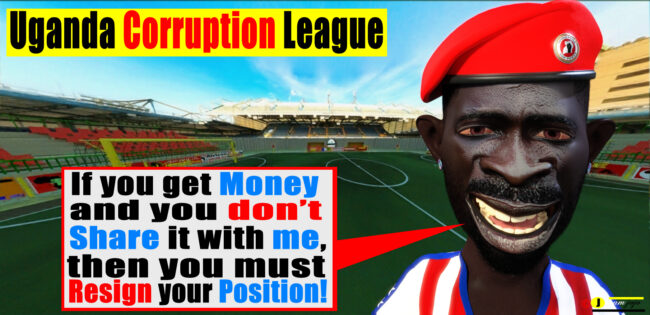

One cannot refer to Uganda as a democracy. Following the brutal regimes of Milton Obote and Idi Amin, power is now in the hands of President Yoweri Museveni where it has rested for the last 26 years. Observers described last year’s election as free, but not fair. Victory at the polls for the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) was only achieved by generous election promises and an expensive campaign, funded from state coffers.

Milton Obote was prime minister from 1962 to 1966, president from 1966 to 1971 and from 1980 to 1985

Sarah Tangen heads the Kampala branch of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, a German think tank. She views political life in Uganda with some skepticism. “Uganda is not a de facto democracy,” she told DW, “it is a pseudo democracy with authoritarian traits.”

The military-style police are brutal and they assist and protect the government rather than the people. This is reflected in the poor reputation the police have in the population at large.

Idi Amin was Uganda’s military dictator and president from 1971 to 1979. He deposed Milton Obote.

Tangen says corruption is another of the country’s problems. “There are a large number of paramilitary organizations that operate outside the law,” she says.

Powerful president, divided opposition

President Yoweri Museveni has run Uganda since he came to power in 1986. When he was taking the oath of office, he said that Africa’s problem was that its leaders stayed in power for too long, thereby encouraging impunity, corruption and cronyism. When journalists remind him about his length of time in office, he replies evasively “It’s a question of fighting.” Museveni said he has been fighting his country’s problems since 1971, in other words since Idi Amin seized power. “We fought for 16 long years, do you expect me to give up half way? Because we are still fighting, not in the bush but in the government. I am not talking about power, I am talking about the struggle.”

Museveni sees the presidency as a life-long mission. He believes he must adopt tough measures to stop the country from sliding into chaos. The reason why he is still in power is because the opposition is divided, it lacks a coherent political strategy. It has failed to win the support of the masses, even though the country has seen anti-government protests against high food prices, corruption and social inequality.

At the crossroads for half a century

Kizza Besigye, formerly Museveni’s personal physician, is the country’s strongest opposition leader. He believes his country has made progress on infrastructure and the economy generally, but not in its political life. Fifty years after independence, Uganda is still at the crossroads, Besigye says. “We still haven’t succeeded in making the transition to a stable, democratic society. In those 50 years, there hasn’t been one single head of state who has handed over power to his successor peacefully,” he added.

Democratic rights may be written into the constitution, but the reality is rather different. The right of assembly has been drastically curtailed. Permission for demonstrations is often denied on the flimsiest of pretexts, protests are brutally put down by “security forces”.

Rights groups persistently voice concern over the discrimination of sexual minorities in Uganda

Agnes Kabajuni works for the rights group Amnesty International in Uganda. “We are very concerned by the many human rights violations that take place here,” she says.

Beacons of hope

The government adopts a antagonistic attitude to NGOs like Amnesty International. Activists who campaign for the rights of sexual minorities bear the brunt of such hostility. One of the country’s best known gay rights activists, David Kato, was murdered last year. The culprits haven’t even been found, let alone put on trial or convicted. Kato was instrumental in ensuring that draft legislation which envisaged the death penalty for gays and lesbians was eventually dropped.

It was also pressure from the international community that forced the regime to abandon this draconian bill. Such pressure is still needed. “We need support, urgently.” said Clare Byarugaba from the NGO Civil Society Coalition, which fights for gay rights in Uganda. “We believe that draft law was scrapped because the government was worried about its image,” the young activist believes.

The majority of Ugandans are under the age of 20. The only president they have ever known is Museveni and they are calling for their rights with increasing self-confidence. Young parliamentarians are also starting to become more vocal in their criticism of the regime, which is a sign of hope in the former pearl of Africa.